I had originally hoped to begin a series on comic artist Shirato Sanpei by looking at arguably his first “important” work, Ninja bugeichō (Handbook of Ninja Arts), but given the recent passing of Nakazawa Keiji on the 19th of this month from a prolonged battle with lung cancer, I felt it might be more appropriate to begin with Kieyuku shōjo (Disappearing Girl, hereafter KS), the story of a young girl whose mother succumbs to radiation sickness (genshi-byō) or what we might call radiation poisoning from the fallout after the bombing of Hiroshima. The girl, Yukiko, too was exposed, and her illness repeatedly gets in the way of improving her ever deteriorating situation in the postwar period.

As a hardcore fan of Shirato’s work, it pains me to admit that I don’t think KS is particularly good, or at least not the first half, because, as Nakano Haruyuki notes in his essay appended to the first volume, Shirato largely sticks to the conventions of the “sick girl down on her luck” plot (more than likely a wide spread aping of the “Matchstick Girl” story) that was then (1959) common in shōjo manga, a trope that is much better done later by Takahata Isao in his animated adaptation of Hotaru no haka (Grave of the Fireflies) by Nosaka Akiyuki. The innocent Yukiko is bandied about by cruel and deceitful people whose indifference to her plight sends her spiraling ever downward until she is “rescued” by a mountain man (lit. yama-otoko) at the end of the first volume. It is from that point on that it becomes clear that Shirato is manipulating certain narrative conventions for his own political ends, particularly to bring to light the discrimination that many hibakusha (bombing survivors) suffered (and still do suffer) under as well as protest against the U.S.’s continuing development of nuclear weapons, particularly with the testing of the hydrogen bomb on the Bikini Islands in the late ’40s and early ’50s. Though one of Shirato’s earliest independent works, Kieyuku shōjo reflects many of the ways in which he would later use what might at first seem to be conventional manga storytelling (especially his works concerning ninja in the Sengoku and early Edo periods) but is transformed into a kind of protest art that is both populist and popular in a way that the “serious” manga of the gekiga workshop was often not. I will have more to say about this next week, when I delve into Shirato’s and his father’s background as proletarian artists.

Legacies of the Bomb

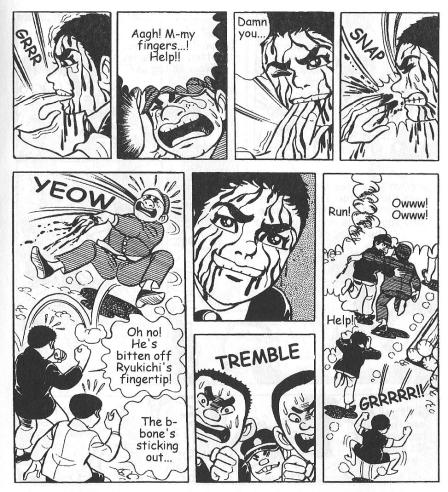

Though both Nakazawa’s Hadashi no Gen (Barefoot Gen) and Shirato’s KS both deal with the legacy of the atomic bombings of Japan, each emerges from a very different milieu and serves a difference purpose. Nakazawa’s work seems more in line with John Whittier Treat’s notion of “victim’s history,” i.e. a tale of innocent suffering at the hands of forces wholly beyond one’s control, or the genre of witness literature that is now, for better or worse, all the rage in academia. Though Susan Napier applies this mode of reading to Gen, having taught the manga myself several times, it feels as if she misses an important subtlety of Nakazawa’s text (in part because she is only dealing with the later feature length adaptation), namely that Gen levels a critique against the brutality of Japanese society in toto, not just those “bad guys” in charge who victimize the otherwise helpless populace. When Gen’s sister is stripped naked and humiliated by her principal, under suspicion that she had stolen money, her father flies off the handle and beats the principal into admitting that he was wrong. Similarly, Gen and his brother react to a very real slight by biting off the fingers of their offenders. No one seems to suffer “innocently,” if one understands that Nakazawa’s text depicts all parties, both the more and less virtuous, as susceptible to the violence and cruelty of a nation mobilized for war. Moreover, Gen figures prominently in Japan’s larger memorial project in and surrounding Hiroshima, both as place and idea. At the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, images from Nakazawa’s work are prominently displayed in exhibits, and one is encouraged to purchase Gen in the museum’s bookshop.

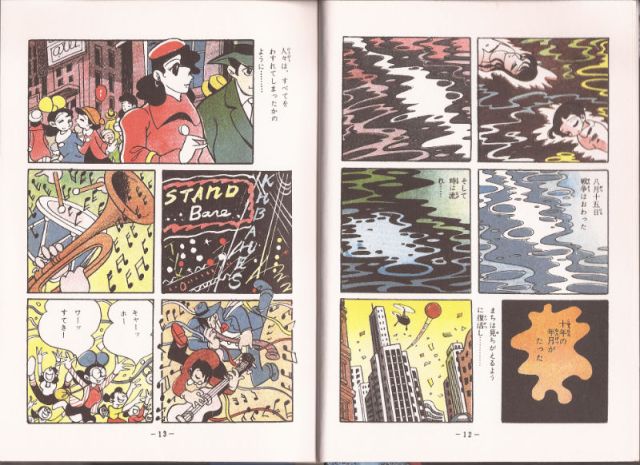

KS, on the other hand, does not feature at all in this memorial project, in part because it was not particularly well known until its recent reissue in 2009. KS also isn’t too concerned with the event of the bombing itself or the immediate aftermath. From the end of the first volume of Gen graphic images of the atomic fallout and people’s struggles to survive solicit reactions of anger and disgust at what happened. That the events of August 1945 are, as represented, “true ” and “faithful” from someone who was actually present in Hiroshima at the time is an important underpinning of the text. KS, however, is fiction and, as I say above, sticks closely to the conventions of a predetermined form of storytelling. In fact, the events of August 6 are presented quickly at the very beginning of the text before moving to ten years later, when the story is actually set. What is striking in those initial pages is the juxtaposition on page twelve of bodies floating in the river in 1945 with the hustle and bustle of “the town” ten years later.

p. 12 – “August 15, the war has ended / And time flows on…… / 10 years have past (lit. 10 years of months and years have past) / The town is hardly recognizable in its revival……”

p. 13 – “It’s as if people have completely forgotten everything that happened……”

The tension between the “peace and quiet” of Hiroshima and its people in ruins and the raucous busy-ness of a somewhere-else is palpable, making clear that what concerns Shirato is not eye-witness testimony–an I-was-there-so-I-know account of what it was “really like”–but an unearthing of that which Japan’s rapid recovery following the war had invisibilized. Kurosawa’s Stray Dog is perhaps a more compelling take on this theme, but in 1959, long before Nakazawa’s grittier take on the collective memory of Hiroshima, Shirato is to be commended for keeping alive the memory of things that the government and population were all too willing to forget, part of the implicit bargain with the Allied Occupation to rapidly rebuild the Japanese economy so long as that development accorded with British and American interests. As a Marxist and the son of a prominent Marxist, Shirato likely saw no difference between the Imperial and later Occupational governments’ censorship of socialist art and literature. Something that has always annoyed me about Gen is how it bends over backwards not to blame the U.S. for anything it did to Japan during the war and how it tries to lay all responsibility for the war at the feet of the Japanese. Shirato, on the other hand, is not afraid to criticize the U.S. and show solidarity with those protesting nuclear testing in the Pacific on the comic’s final page.

Do you know the Mountain Man?

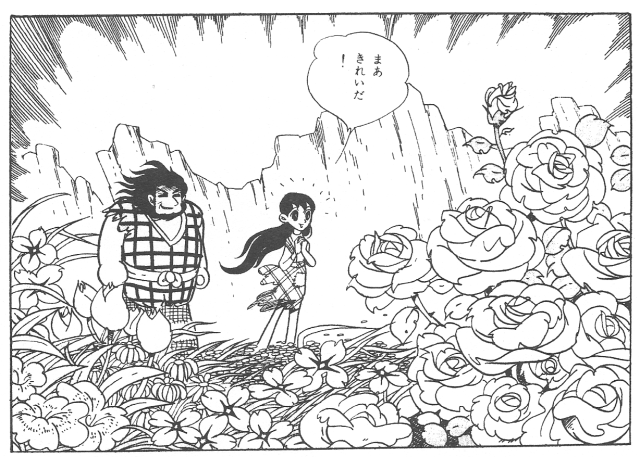

The second volume of KS removes Yukiko from “the town” (whose location is never specified) to an (equally unidentified) idyllic, pastoral setting by the “mysterious mountain man” (nazo no yama-otoko) who rescued Yukiko from a mob of children and dogs who were harassing her at the end of the previous volume. When we first see the mountain man, he is presented as a sinister type, savage, wrapped in animal skins, and leering menacingly over Yukiko’s unconscious body. A little girl–this is, presumable, shōjo manga, after all–might be forgiven for thinking that something horrible is about to happen, but the first thing he says (or thinks, rather) as he lifts her up is “She’s injured…… / Poor thing……” (ケガシテル……/カワイソウニ…… – vol. 2 p. 23). I choose not to transliterate the Japanese, because the use of katakana points to an ambiguity in the mountain man’s character. Initially this use of nothing but the secondary Japanese syllabic script might indicate his savagery or otherness. At any rate, it’s meant to indicate that there is something not quite right about his command of the language, even though the mountain man speaks perfectly grammatical, if clipped, Japanese. For, after the mountain man nurses Yukiko back to health, and they begin to live an idyllic (isolated) life in imitation of man and wife, he reveals to Yukiko that he is not Japanese at all but Korean. Ten years ago, his village was raised by Japanese soldiers and he was conscripted into forced labor in a mine. When one day a tunnel collapsed, he was able to escape to a cave on the other side, and there he has lived ever since; he didn’t even know that the war was over until Yukiko informs him of the fact, when he finishes his story. The two have a hearty laugh about it all, and it seems that Yukiko has finally found someone and somewhere to comfort her in her affliction.

But a life of peace is not to be for either Yukiko or the mountain man. Hunting in the woods one day, he is discovered by a man in dark glasses who identifies him correctly as Rī Kidō (I have no idea what this would be in Korean) and apprehends him. Later, a tubby bureaucrat tells the mountain man that because he is not a Japanese citizen, they must return him to Korea, an irony to be sure considering he was brought to Japan by force in the first place. I should note that nowadays it would not be uncommon to hear about the condition of resident Koreans (so-called zainichi) in Japan even in popular media, but in 1959 the subject would have been very much taboo. Again, the mountain man escapes from police custody, and tries to determine what has happened to Yukiko in his absence. It is not until a nurse unceremoniously notes that Yukiko’s room at the hospital is being prepared for the next patient that the mountain man realizes she has died. Yukiko, the central character of the story, passes without notice, and Shirato repeats, intentionally I think, the brutality to which she has been subject for the entire text, for it is only by taking on the conventions of the “sickly girl” plot that Shirato can undermine them. The mountain man wanders off into a swirling storm, never to be seen again, something clearly echoed later with the character of Jūtarō in Ninja bugeichō.

Stay tuned!

Ba Zi

contact me: uahsenaa@gmail.com

Leave a comment